This post represents a strengthening in my critical position of academic mystification which, I submit, is usually achieved by means of excessively complex jargon. Perhaps in reaction to this sin of scholarship, I utilize informal language and engage in frank self-disclosure, possibly verging on the contextually inappropriate. While I condemn Berger (and Galloway) for academic posturing and distantiation, maybe I am “regular Joe” posturing and trying too desperately to connect. This would make us — Berger, Galloway, and me — not horses of a different color, but two sides of the same coin. And considering my “corruption” by years of higher education, such a characterization is probably more accurate. I end with a call to find some middle ground between “folks” and “philosophers,” the School of Life and Life in School. I hope that my work always reflects my honest effort to bridge this distance.

Ways of Communicating: Response to Berger’s (1972) Ways of Seeing. (originally posted to class wiki on September 8, 2010)

“Our goal should not be to model books on television or television on books but instead to discover the most rigorous, stimulating and sophisticated ways to take advantage of different platforms’ unique capabilities” (Kozberg, 2010).

I agree entirely with Alison’s well-turned phrase, and find that it echoes Thembi’s observation in class that utilizing HootSuite in order to simultaneously update your profile on various social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Buzz, LinkedIn) is tantamount to spamming. What both of my fiercely smart classmates are arguing, I think, is that there is such a thing as message-platform appropriateness (see Media Richness Theory, Daft & Lengel, 1986). You don’t share exquisitely detailed technical instructions face-to-face, you don’t interview for a job via text, you don’t deliver hash-taggy URL’s to your online resume, and you don’t deconstruct the visual via print.

Am I reading you right, ladies?

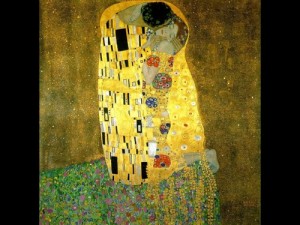

It’s difficult to really appreciate our myriad ways of seeing when all we’re seeing is text, and imprecisely written text at that. Like Alison, I bristle at the gender essentialism (which was present even in the television show — his claim, “Men dream of women; women dream of themselves being dreamt of. Men look at women; women watch themselves being looked at… Women constantly meet glances, which act like mirrors, reminding them of how they look, or how they should look. Behind every glance is a judgment” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u72AIab-Gdc, first minute).) that ran rampant through this book’s pages.

I feel a real frustration with the language of scholarship, particularly art scholarship. What is our objective here? Are we trying to communicate, really, or are we just trying to say a lot of things that maybe sound smart to the stupes who are impressed by polysyllables?

At dinner tonight, my aunt told me that she couldn’t understand an email I sent. Friends who are NOT in academia did understand it, and I swear to whatever, I broke down my studies as simply as I could, but that’s the kind of statement that gives me chills:

“I didn’t understand a word of it. Do they teach you how to write that way?”

She tends to exaggerate, my aunt. Let’s all acknowledge that. But heaven forbid I lose touch, don’t know how to talk to people outside this ivory tower, jack up my hubris-inflated sense of myself, expound ineffectively for purposes unimportant. Maybe that’s what I should dress up as for Halloween, the pathetic academic — that’s the scary monster that haunts me.

So I take issue with Berger’s TV show too. I know he talked to kids, I know he wore groovy 70s shirts, I know he had a humanizing speech impediment, but… eh? Is it still a little full of itself? Is it still a little distancing? I don’t know, I really don’t. I like how he juxtaposed classical art and contemporary video — great way to make connections and keep the old relevant… Ah, but this space is for figuring things out, right? For ruminating and experimenting? If I put such imprecise ramblings on limestone, that’d be message-platform inappropriateness. Oh! And it all ties together…

But seriously, I’m struggling. I certainly don’t want to limit scholarship or imply that intelligence/expertise should be cloaked. In fact, quite the opposite. Moreover, I find the tide of anti-intellectualism in this country ignorant and dangerous…

Let me digress for a minute. The third-person effect is a communication phenomenon. Researchers have found that individuals tend to overestimate the degree to which other people, NOT their superior selves, will fall prey to trickery/noxious influences. “Oh, sugary cereal ads won’t influence me/my kids, but my kids’ friends will probably be duped and want to buy Glucose Snappers, so let’s pull that commercial from Saturday morning television.” Capische? So I want to acknowledge the third-person effect too — it basically tells us, we’re terrible judges of what other people think and how impervious we’re really not.

Here’s how I’m putting this all together:

Maybe I need to give lay people more credit (and regard my aunt as the outlier). But maybe it couldn’t hurt for us, we in this bookish community, to turn up our vigilance. Let’s make sure we avoid becoming our own caricatures, NOT solely because we assume (perhaps fallaciously) that outsiders can’t understand us and/or that they’re out to financially lynch our industry and/or ridicule our ways. Let’s keep on being grounded and human-speaking in order to ensure that our eyes remain fixed on the all-important prize: using this education to meaningfully contribute.