On June 23, 2012, I had the honor of joining Dr. Rosanne Cordell and Judy Kleinberg on a panel titled “Digital Literacy and Libraries: Designing What Comes Next,” organized by the American Library Association (ALA)’s Larra Clark and Marijke Visser. This panel was moderated by ALA’s Office for Information Technology Policy Fellow, Founding Director and Professor in the Harrington School of Communication and Media at the University of Rhode Island, media literacy expert, and friend Dr. Renee Hobbs. Both attending and speaking at the annual American Library Association Conference & Exhibition in Anaheim, CA, was a phenomenal opportunity to recognize my love of libraries and, importantly, engage in some personal translation and interdisciplinary outreach. I tapped into my personal best.

On June 23, 2012, I had the honor of joining Dr. Rosanne Cordell and Judy Kleinberg on a panel titled “Digital Literacy and Libraries: Designing What Comes Next,” organized by the American Library Association (ALA)’s Larra Clark and Marijke Visser. This panel was moderated by ALA’s Office for Information Technology Policy Fellow, Founding Director and Professor in the Harrington School of Communication and Media at the University of Rhode Island, media literacy expert, and friend Dr. Renee Hobbs. Both attending and speaking at the annual American Library Association Conference & Exhibition in Anaheim, CA, was a phenomenal opportunity to recognize my love of libraries and, importantly, engage in some personal translation and interdisciplinary outreach. I tapped into my personal best.

As I briefly mentioned during the talk, my Grandma Elly was a children’s librarian at Chicago’s Linne Elementary School. My mom worked at the Northwestern University library when she was an undergraduate. In fact, my parents had just started dating when Mom was hired over Winter Break, 1971-72, to transfer the books from old, Hogwarts-esque Deering Library to the new, dystopia-inspired towers of terror; Dad used to visit her there. When I was a kid, the local library was a magical place of unlimited books and videos. One year for Halloween, I dressed up as the princess character from a Glenview Public Library-based reading incentive game. When I graduated from Northwestern University, I worked in the media section of the Northbrook Public Library. In Somerville, I adored the community library in Davis Square and the university library (with its new coffeeshop!) at Tufts. After my first roommate in Los Angeles flew the coop, my love of the Los Feliz Public Library motivated me to find a new apartment in the same neighborhood. And there’s no better place to hear the soothing sounds of a fountain (but not to plug in your computer or read from your sun-glared screen) than the courtyard outside Literatea at USC’s Doheny Library. I.LOVE.LIBRARIES. But that’s somewhat tangential.

During the digital literacy panel, despite the fact that I had hardly slept the night before out of excitement for an upcoming milestone (or because of my jittery joy?), I was on fire. I felt inspired by Renee’s concerted effort to connect with the audience and explain concepts in comprehensible, engaging ways — no jargon, no monotony. I also reflected on my dissatisfaction with conferences in general as they fail to honor and optimize the potential of the people present. Attendees sacrifice dollars, abandon families, up-end work schedules, and expend carbon — for what? Not to be read a paper or hear its highlights — they can read the text or abstract via PDF in the comfort of their own homes. Not to listen to a one-way presentation — they can be talked at via YouTube, once again, in the comfort of their own homes.

In the internet-less past, easy distribution of articles, lectures, and slideshows was impossible; thus, such a 1.0 approach to conferences was rational. But that isn’t the case anymore. Now we have the internet; moreover, we have a 2.0 internet. We have opportunities to be seen and to talk back via Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Reddit, Pinterest, Posterous, tumblr, etc, not to mention such niche-specific sites as COMM.init, TeacherTube, and DMLcentral. So what is the point of gathering together in one room today? How do we justify the financial, familial, professional, and environmental impacts?

My answer: Connection. Give-and-take between the attendees and the presenters, and introductions and dialogue among the attendees. Let’s tailor and respond, let’s network and collaborate, let’s get out of going it alone and benefit from the power of collective intelligence.

I think that’s what we did. I invited participants — my preferred term to attendees because it implies less passivity — to show me and each other who they are. I encouraged them to talk with partners and join teams with other pairs. I welcomed them to share their discoveries with the group. Later, Renee requested at least six participants share their (realistic) magic wishes, then had every participant fill out an index card (or exit ticket) identifying their biggest takeaway and remaining question(s).

This was co-learning, I believe. This was conference 2.0.

Additionally, my extemporaneous speaking about my passion for play came out eloquent. Was I proud. I felt like I’d finally made a convincing, accessible case for the importance of play. And maybe all I’d needed all along was to speak to people who would listen, and listen to people who were (finally?) empowered to speak.

In deference to this magical experience, and in the hopes of articulating a dissertation prospectus, I transcribed Renee’s prompts and my improvised answers from a recording I began making after six minutes had elapsed, once I realized that Renee’s lecture was gold.

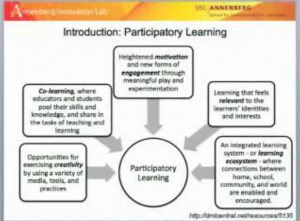

RENEE HOBBS, 15:15: And finally we have Laurel Felt, a doctoral student at the Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism. She was involved in developing the curriculum for the project called PLAY! — Participatory Learning And You! And she also does some consulting for the Shoah Foundation.

So I guess I’ll turn it over to the panel. Why are you interested in digital literacy and what’s your personal connection to it? Who wants to start?

LAUREL FELT, 15:50: I’ll start! Thank you. Thank you so much, Renee. Isn’t Renee an inspiring speaker? [applause] Well, I was struck, actually, by how powerfully Renee spoke and what a good job she did of being an educator, which made me think that I wanted to try my best to emulate. So I wanted to speak a little bit less about me — to learn more about me I welcome you to go to laurelfelt.org. I’d love to learn a little bit more about you. I think that participation is what digital literacy is all about. So let’s find out who we are.

If you identify yourself as a , please raise your hand.

If you identify yourself as a librarian, please raise your hand.

If you identify yourself as an educator, please raise your hand.

If you identify yourself as an artist, please raise your hand.

If you identify yourself as an activist, please raise your hand.

If you identify yourself as a government employee or somehow a vessel of government [laughter], please raise your hand.

If you’re part of the tech industry, please raise your hand.

If you’re part of the entertainment industry, please raise your hand. — It’s the hometown industry. (I came in from LA.)

Excellent, thank you so much.

If you feel confused [laughter] about digital literacy, please raise your hand. [pause] Yeah, that’s why we’re all here. I’m not sure you’re going to walk away with it all clear as a bell, but hopefully we’ll be further along and hopefully we’ll feel more empowered to engage in a conversation, to have a jumping-off point.

If you feel confused about what it’s going to take in order for your institution to be prepared for the 21st century, please raise your hand.

If you’re not sure how best to serve children, please raise your hand.

It’s murky, right? I was looking at the definition that Renee shared and it’s sprawling, and comprehensive, and inspiring. And I have to admit that as she was talking, I went to laurelfelt.org and I edited my homepage. [Previously], I had changed one of my terms from “digital literacy” to “new literacies” because before I thought I’d found a nuance and I thought that new literacies was a better umbrella to encapsulate all kinds of different ideas, but when she articulated everything that she found to be salient to digital literacy, I thought that was the best umbrella you could find. [And so I changed it back to “digital literacy.” POST-SCRIPT: I have since changed it to “new media literacies” in order to reflect my Jenkins-ian lineage.]

And I feel like those two things that occurred — this evolving idea of what we’re talking about and this ability to change our online representation, and to do it at a moment’s notice — is all part of a new culture that is remarkably different from even the one I grew up with, and I’m 32 — which is old to kids today. It’s even old to my college students; I’ve got 10 years on the oldest ones.

I think that when we’re evaluating digital literacy, what we need to remember at the same time is that people are people, at our hearts. And we sometimes feel intimidated by all of these tools. But people are tool-using creatures — that’s how we define “man” in a classical anthropology sense. And just because the tools have changed doesn’t mean that we need to throw out the baby with the bathwater, and that the world is falling apart. We just have to figure out how to master these tools for our own ends, and not let them rule us.

So I guess I’ll use that as my point of departure.

RH, 28:05: Okay, so let’s see if we can drill down on this issue of definition, which we said we would play with. I guess, my question to the panelist is, Do we really need a definition of digital literacy? Why or why not? If it is emerging, maybe we should just let it emerge. I’m curious about your take on what are the pro’s and con’s of nailing down this sprawling set of concepts. And my second question is, Should academic, school, and public librarians be responsible for all of this, or for part of it? What role should librarians play, given the diverse stakeholders coming to circle around this concept?

LF, 31:44: Hi, everyone. Renee instructed us to be provocative, and to make this lively, so I’m going to throw a few provocations out there.

I’m reminded of my studies in child development and, according to some, unless you have a word for something, unless you have language, you can’t see it, and you can’t remember it. And some people say that lack of language is partially responsible for why very young children have no memory. It’s not only that they’re developing cognitively but they’re not sure how to discern or distinguish one object from another and tag it and file it in their brains so that they can pull it up later. So if we don’t have a word for what digital literacy is, then how will we be able to see it when it’s happening? Or see it when it isn’t happening? Or begin to drill down on it?

Sometimes by calling out all of the constituent things that occur in a process, we’re able to give it more value. For example, sometimes people write off the occupation of housewife. But when you start to articulate what it takes to be a housewife, you’re actually a nurse, you’re a chauffeur, you’re a custodian, you’re a therapist, etc, etc, etc — well, that’s a heck of a job. So I think that it could be very productive to put out some guidelines so we have something to recognize and something to aim towards.

I recognize that language can be restricting and so now it makes me want to re-edit my homepage, to tell you the truth. Now I want to say “new literacies” acknowledges that there’s a march of progress that I think Renee threw up very eloquently on her slide. That literacies continue to emerge and perhaps that’s the umbrella term and digital literacy’s underneath it, and “digital” will keep on changing but “new” will acknowledge that we evolve.

In terms of what role librarians play, or what role teachers should play in part of this or all of it, I’d like to throw that back at you. So I invite you to take about 20 seconds to think about it. And then turn to your partner to discuss, so someone who’s on your left or your right. Ready to start thinking about it?

RH: What are we discussing?

LF: What role does a librarian play in supporting digital literacy? Okay, turn on your thinking caps. Okay and whenever you’re ready, turn to somebody next to you, maybe you already have, talk it out.

…

And if you’d like, you and your partner can find another pair and make it a conversation of four.

…

If you can hear me, clap twice. If you can hear me, clap three times. If you believe I taught preschool, clap four times. For four years! [laughter]

Thank you so much, I hope you enjoyed your conversations with each other, it looked so lively. I would like to invite you to do two things. One, for those who are bold and interested in sharing in this space, I’d love a representative from your group to come up, introduce yourself, and tell us what you were talking about. And for those of you who don’t have the time or can’t make it up to the microphone or prefer not to speak in public, do know that we have a hashtag on Twitter — it is #digilit – D I GI L I T.

RH: 12, digilit12.

LF: I’ve been doing it wrong! Oops. It’s all safe, I can just copy and paste. So you can do #digilit12, so that’s #digilit12, D I G I L I T 12, and share some of your impressions, your ideas in that space as well — this is the richness of the new digital world we’re in. But for now let’s maximize the fact that we’re all together in one space. Who would like to come up and tell us what you were talking about? Come on up. And there’s a microphone here.

PARTICIPANT 1 (Kim): Well I was just talking with one other person. I’m in a semi-interesting situation in that I work at… which is an all online, for-profit institution. I always feel a little bit alone in a crowd… As to the question, Do I feel like we have a responsibility? … Absolutely. As an open admissions, online, for profit… it’s not just that it’d be nice to have, it’s a must that we need to put it out there. But as my discussion partner was saying, it’s a shared responsibility, especially with adults like we have, they have to go out there, they have to watch the videos, they have to view the tutorials. … If you’re bringing people into the platform, you need to make available the tools so they can understand how to use other tools.

What gets difficult is when any kind of learner, when they need information, they get more overwhelmed the more information you give them. Question, How best to present the information in a way that is timely and manageable.

LF: That’s true. Thank you, Kim. So I’d love to invite someone else to come up and I’m just going to reiterate what I heard while that person comes. Who would like to be next? [pause] Great. So what I heard from Kim is this notion of shared responsibility, that we’re all in this together. But I feel like I also heard an ethic of, sort of, responsibility, of stewardship, “if WE are going to offer something to THEM…” It implies a sort of hierarchy, then we need to be able to sort of scaffold that experience, which is interesting. And then the question of pedagogy — so how best to teach and not overwhelm. These are great questions, thank you, Kim.

PARTICIPANT 2 (Nicole): Hello everyone, hi Kim, I’m Nicole, it’s nice to meet you all. So in our discussion group we talked about the fact that, because of the magnitude of what digital literacy is all about, and the role that libraries have, it’s something like you said, we cannot do it alone, and we discussed the importance of collaboration and working with our community partners, stakeholders, government, academics, schools, in order to make it happen. We also discussed the fact that, whether we want to take on the roles, we are forced to do that because of the demand we have in our libraries and institutions from folks who really need these services. And then I think the third aspect that we discussed was the fact that this is only one aspect of literacy. We work with lots of different populations who have a need for language literacy and helping folks first to understand the language and then, as a next step, understanding digital literacy. So it was those three areas that our group discussed.

LF: That’s wonderful, thanks, Nicole. I feel like everyone in this room could be up on this panel. Very brilliant ideas. So what I heard from that is the notion of coalition-building and trying to form vibrant relationships, hopefully steeped in understanding, respect, functional communication with all of the stakeholders who Renee enumerated. There’s also the idea of sort of being forced into a corner if you will, it’s not a question of want to, it’s a question of have to, that the ground is shifting beneath our feet and we need to respond. And I feel like I also heard the idea of preparation, that in order to be able to access some of these higher order skills most productively, there are some other skills that are necessary in order to get there. So you need to be able to use language and, my bias, is that you need to have social and emotional competence: self-awareness, self-regulation, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. So those are the things that help to set the stage, intrapersonally and interpersonally, for productive work of all sorts. So, where does that fit into the mix? Does that happen while we’re doing digital literacy work? Before it?

Now I’m going on my own tangent, you didn’t say all of that.

RH: Take two more comments, Laurel, then we’ll move on.

LF: All right, well, Judy had a great question. Remember, your “a-ha”?

JUDITH KLEINBERG: Oh yeah, my question was for you. Did you, in your conversation, come to some clarity, some a-ha moment? What was that “a-ha” that you didn’t have before you started your conversation.

RH: Come up to the microphone and share your a-ha.

PARTICIPANT 3: Digital technology is changing the way we work… [difficult to hear]

RH: That’s a great a-ha moment. Thanks for sharing!

PARTICIPANT 4: So our a-ha moment wasn’t — the opposite of that…Tablet, book, scroll, CD-ROM, Internet… modes have changed, at our heart we’re still doing the same things.

LF: They’re with our program, Renee, they’re trying to be provocative.

RH: Are there any more a-ha’s?

LF: Take it, Mary Alice.

PARTICIPANT 5: …School librarian. Students know technology better than she does. I taught in a library school… I believe we have to do things… always ready to humiliate ourselves… Do something that you don’t have a clue how to do.

RH: Wonderful insight, last a-ha…?

PARTICIPANT 6: Mine is — my own, sorry — my a-ha moment is that we need to fight… We had to fight for banned books… I’ve been telling you for five years, SWe need e-readers. So you know what I did? I went out and bought them myself. So I could teach. And that’s sometimes what we have to do make it happen… So that became the most popular class, the library is … sometimes we have to scream and yell and kick our feet to get the tools we need to teach the things that people need to learn.

RH: Absolutely wonderful. So in a way now we want to address kind of the consequences of that a-ha moment which is, What are the gaps, the challenges, the silences, and the omissions around what we SAY about digital literacy and what exists in practice? So I think it’s important for us to be REAL, that’s there’s a lot of hype on this topic. The tech industry is telling us, Everything will be great and glorious if only you get that latest thing. And we all kinda want to believe that’s true. And we want to see ourselves as “in the game’ with digital literacy. But we all recognize the gap between our aspirations and where we are right now with the practice. So I’m going to ask the panel members to talk a little bit about how you see the gaps, the challenges, the silences, and the omissions. Because once we get some precision and clarity with that, then we can decide what to do about it.

LF, 55:40: I have to stand up. [laughter] I used to do improv comedy, I still sort of do, and so what I’m feeling like are some of the gap are passion and fun.

If you feel like we’re being too serious overall, turn to your partner and give em a high five. [laughter] Renee?

You know the way that every child learns is through play. And we spend so much of our time as adults seeking out entertainment and pleasure. And information can be a pleasure. And engaging in digital spaces can be a place where we experience flow, which is when you lose grasp of who you are, where you are, and you’re just immersed and you lose yourself. Isn’t that a great feeling? That’s how some people feel when they play a game, when they’re listening to music, when they’re reading a good book — you librarians, probably you guys –, when you’re watching a movie. And I think it can be how some people feel when they come to the library or when they’re sitting in a classroom.

But I feel like we’re making this really scary and we’re making it all really technical. And we need to lower the barrier a little bit and allow people to play more — to touch tools, to see what happens when you touch this, when you go here. And I think that in order to liberate the pedagogical process that you’d spoken about earlier, and avoid the information overload, what we need to do is to encourage people to play, and to go find the answers to their own questions, and trust that they’re going to do that in a way that feels safe and comforting and even enjoyable.

Maybe only 10% of us raised our hands when I asked if we’re artists. Every kindergartner is an artist! So what happened? And now that we all have these creation tools, what excuse do we have? I think that we can aspire to bring back some of the passion and the fun and the play, and that can be very meaningful and help us to collaborate better, to lead healthier, happier lives, and to optimize the potential of digital tools and of analog tools — because to get ready to interact in digital spaces, you don’t necessarily need one of these [holds up an iPhone]. And by the way, this costs $130/month, it’s ridiculous.

In order to do some of the things that are most important online, like seeing what happens if you do something different, you can do that with a peer, you can do that with a ball, you can do that with a book if you turn to any page and have to read the first line (so that’s sort of an improv game).

But you see what I’m saying — that in order to ramp up to use the digital space productively, there’s a lot of things that we can do with no money down, on the ground, in an analog way, and that can actually be harder — changing the way that we think and the way that we do things.

Some thoughts.

RH: How fascinating. So now I’m going to ask the panelists to pretend that you have a magic wand, here it is. But it’s a realistic magic wand in the age of an economic recession, double digit unemployment, and the realities, all of the realities of 2012. When I pass you the magic wand, you are granted one wish and it will come true. But it has to be a realistic, do-able wish. If you could wave your magic thing and do one thing, Judy, what would it be and why? -With the goal of making all Americans digitally literate — don’t ask for a million dollars here.

LF, 1:04:07: I wish for more wishes. [laughter] I’m thinking about libraries. I love libraries, I always have — my grandma was a librarian, my mom worked at the college library when she was a student, when I graduated from college I worked for a library…

I was at a really interesting panel this morning and they’re talking about how they’re striving to de-clutter their libraries, make their shelves lower, get rid of some of their reference collection because it’s online, and what that opens is space: space to do; space to connect with one another. I would love to see more spaces to play, with librarians being the champions of play. Because play is really the scientific process and it’s bathed in information.

One of my mentors, Henry Jenkins, and his colleagues define new media literacy play as “the ability to experiment with your surroundings as a form of problem-solving.” So seeing what happens when you do something. And I think that that’s inquiry. It’s, “Hunh, I wonder what will happen.” You examine it critically, you’re a keen observer, you note what occurs, you catalog it, perhaps that leads you to apply it in a certain way, to unpack it a little bit further, to ask another question — that’s research. It’s also play. The two reinforce one another.

In urban environments and rural environments, we’re seeing an erosion of playgrounds. And people worry that the entry of digital into our lives means that we’re becoming automatons — that we’re not using our bodies, that we’re not using our brains, that we’re just being dulled and passively consuming. It would be amazing to push back at that and to bring back play with our whole bodies, with our whole minds, and for libraries to be a haven for that, and for librarians to lead the way with tools that we can play with. That includes really serious technical things, like a computer, and that also might be kind of playful and that will help to unlock creativity and lead to questions, like toys and puzzles and sensory things.

I led a workshop with City Year and you wouldn’t believe what kinds of ideas people came up with when I gave them a whole bunch of animal figurines. Well, they were stunned — What am I doing with animal figurines, giving them to adults? But they used them to model some issues that they had with their communities and it helped them to think outside the box. [It also helped them to laugh together and bond as colleagues.] And that’s what we’re all trying to do, right? “Innovation, that’s the way forward”? So that’s what I would love for libraries to do, to really honor and embrace and forward play.

RH: Okay so now it’s your turn: You want every citizen, every person you reach in your role as a librarian to be digitally literate and I’m giving you the magic wand: one realistic wish. Come up to the microphone and share with us what you wish for, what would help you create digitally literate library patrons, learners, citizens, in the place where you do your best work.

[Participants share their wishes and the panel concludes.]