During the summer of 2010, I had the thrilling opportunity to work in Dakar, Senegal, with innovative non-governmental organization le Reseau Africain d’Education pour la Sante (RAES) program, Sunukaddu. To this teen workshop in multimedia health communication, I brought a pedagogical model and method that positioned new media literacies (NMLs) and SEL skills as fundamental to meaningful learning, and asset appreciation as key to sustainability. Collaboratively as a Sunukaddu team, local staff and I generated: a daily schedule that reflected a scaffolded methodology for optimizing participatory learning; a programmatic schedule that introduced key communication characteristics, strategies, and platforms, as well as useful theory; full lesson plans that respected our theoretical, temporal, and curricular goals; and a sense of togetherness, prompting us to declare the important Wolof phrase, “Nio far!”

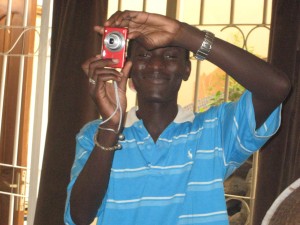

My colleague Tidiane Thiang, 27, an audio/video specialist at RAES, ardently embraced the “Sunukaddu method.” His journey inspired this account (from Dura, Felt, & Singhal, 2012, What Counts? For Whom? Cultural Beacons as Grassroots Communication Measures):

“The Kitten Who Became a Lion” in Senegal

…Prior to joining the implementation team for a new youth development intervention, Tidiane always kept his speech to a minimum. At meetings, he listened attentively and took copious notes; periodically, he would send a long email to the director that articulated his perspectives on the various topics of discussion. Such communicative behavior might be considered Tidiane’s “baseline.”

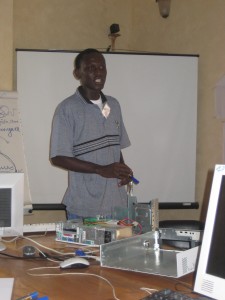

During the summer of 2010, Tidiane and several co-workers piloted Sunukaddu 2.0, an intervention intended to empower youths by supporting their development of skills that enable exploration, collaboration, and meaningful communication (Felt & Rideau, forthcoming). Not only did the program significantly impact participants but its effects upon Tidiane were also profound. During brainstorming meetings and curriculum workshops, he voiced his own ideas. When the program opened its doors, he challenged participants with critical thinking questions and rich cultural commentary. During a lesson on message dissemination, he spontaneously sprang from a corner of the room and translated a lengthy explanation of Everett Rogers’s Diffusion of Innovations theory (1962/2003) from (imperfect) French into participants’ native Wolof. And when unanticipated transportation and scheduling issues left Tidiane as the sole instructor for an entire day, he independently delivered – and innovated! – the curriculum, then enthused about his experience afterwards. In Tidiane’s own words:

“You gave me self-confidence thanks to these skills” (personal communication, September 22, 2010).

“My favorite skills are negotiation, self-awareness, and social awareness because they represent values that are and must be the basis for an equitable and responsible society” (personal communication, September 27, 2010).

Tidiane did not revert to his quiet ways after the program bestowed certificates of completion upon its participants (an element suggested and designed by Tidiane). Rather, he declared his intention to realize his filmmaking dreams by proposing a short video that would explain how to take the skills presented in Sunukaddu 2.0 and adapt them to an African, specifically Senegalese, context (personal communication, October 7, 2010).

When anticipated funding streams fell through, he was undeterred: “I will make it with my own funds because it’s a good subject for a film” (personal communication, January 8, 2010). Tidiane’s colleagues playfully nicknamed him “the kitten who became a lion,” a moniker that he embraced. On August 18, 2010, Tidiane Photoshopped his Facebook thumbnail so that the image of a roaring lion overlaid his polo shirt (See Figure 9).

Figure 9. Tidiane publicizing his newfound leonine identity

Tidiane’s experience functions as a cultural beacon because its full understanding, its very recognition, requires cultural participation. Had outside evaluators visited RAES and observed Sunukaddu 2.0 in action, they would not have noticed anything remarkable – a young instructor was simply teaching a lesson. The phenomenal nature of Tidiane’s speech would have been invisible to these context-less recorders and so this rich data, bursting with implications, would have been lost.

I left Senegal in August of 2010, bidding adieu — but not goodbye — to my beloved colleagues. Here’s a final goofy photo of me, Tidiane, and Brock (a Master of Public Health student at UCLA and my roommate for one month of my stay):

In my absence, Tidiane and our colleague Idrissa, who we both affectionately referred to as our father, continued to share the Sunukaddu method. On February 1, 2011, Tidiane sent me nine huge photo files; each depicted an image of employees from Senegalese non-profit organizations as they used the Sunukaddu method in a training workshop that Tidiane and Idrissa led. Here are screenshots of two of these photographs:

On June 8, 2012, Tidiane sent the following via email:

“Je voulais t’envoyer les photos de la formation sunukaddu que nous sommes entrain de faire à Mbour…

“C’est super de faire sunukaddu à Mbour parce que c’est une zone touristique et c’est l’endroit ou le taux de prévalence est le plus élevé au Sénégal et aussi la pauvreté fait que les touristes on du pouvoir par rapport aux habitants locaux…”“I’d like to send you the photos from the Sunukaddu training that we’re in the middle of doing in Mbour [a city in Senegal approximately 81 km south of Dakar, also along the Atlantic coast]…

“It’s great to do Sunukaddu in Mbour because it’s a tourist-y area and it’s the place where the tax rate is the highest in Senegal, and also the poverty is such that tourists have power over local residents…”

Here are the images that Tidiane appended:

I, too, kept pushing forward with Sunukaddu. I incorporated NMLs, SELs, and Idrissa’s competence clothesline into an after-school program, Explore Locally Excel Digitally, that I co-created with my colleagues at PLAY!

My work with Sunukaddu also indirectly influences all of the work I have done and will do since, including but not limited to such diverse projects as teaching young children in India to developing digital curriculum for the USC Shoah Foundation Institute.

On May 2, 2012, Tidiane informed me via email that a short film he made with his friends would be shown at an international forum on youth employment in Geneva, Switzerland. In a follow-up email on May 3, 2012, he wrote,

“Je pense que ce film une fois qu’il sera diffuser au forum international à Genève , peut être , changera quelque chose dans les politiques d’emploi pour les jeunes au Sénégal et en Afrique.”

“I think that this film, once it’s shown at the international forum in Geneva, maybe will change something with regards to employment policies for youths in Senegal and in Africa.”

I was impressed and, after I watched the film, even more so. I asked for another version of the film, one that included the credits so that everyone who watched would know Tidiane’s name, and requested permission to share his film on my blog. He agreed with pleasure.

Tearing a page from my mentor Henry Jenkins‘s playbook, I also emailed Tidiane a series of interview questions so that his responses could complement and contextualize his important artistic and political work. Here are the questions and answers, first in their original French, then in English and boldface for our reading ease (NOTE: This was translated by little ol’ (limited) me):

LAUREL: Comment est-ce que tu as pris l’idee a faire ce film?

TIDIANE: C’est Alex qui m’as envoyé le lien pour participer au concours et j’ai participer, j’ai beaucoup d’amis qui vivent cette situation donc s’était très facile pour moi d’écrire le scénario et surtout de pouvoir partager leurs préoccupations avec le reste du monde.

LAUREL: How did you get the idea to make this film?

TIDIANE: It was Alex [the director of RAES] who sent me the link to participate in the contest and I participated, lots of my friends experience this situation so it was very easy for me to write the script and especially to be able to share in their concern with the rest of the world.

LAUREL: Comment est-ce que tu as fait le film — trouver les joueurs, louer le transport en commun, faire de la recherche sur l’issu d’access a l’emploi des jeunes, ecrire le scenario, employer les assistants, payer tout le monde, prendre le camera et le logiciel de montage, etc?

TIDIANE: Tous les acteurs sont des bénovoles et ce sont mes amis. J’ai payé 5000 fcf environ 10 dollars au transport en commun et j’ai filmer dans le car rapide mais on n’avait au préalable fait une répétition chez moi puisque la voiture devait faire un seul tour du quartier avec nous alors il failait faire 3 prises et que tous le monde devaient assurer. Le raes m’a prêter sa caméra et j’ai monter le film à la maison avec le logiciel Sony vegas 7 donc le film a gouté 10 dollars.

LAUREL: How did you make the film — find the actors, rent the bus, do research on the issue of youths’ access to employment, write the script, hire the crew, pay everyone, get the camera and editing software, etc?

TIDIANE: All of the actors were volunteers and my friends. I paid 5000 francs — around $10 USD — for the bus and I filmed inside the bus but we didn’t have any prior rehearsal at my house because the bus had to make one circuit around the neighborhood with us, so we had to do three takes to be sure that we got it. RAES lent me its camera and I edited the film at my house with the program Sony Vegas 7, so the fim cost around $10 USD.

LAUREL: Combien de temps est-ce que tu as pris pour creer ce film?

TIDIANE: Le film m’a pris une journée de travail.

LAUREL: How much time did it take you to make this film?

TIDIANE: The film took me one day of work.

LAUREL: Expliquez plus sur le forum au Geneve. Donnez-moi le nom entier du forum et direz comment tu est arrive a ce point-ci d’y aller et présenter ton film.

TIDIANE: Même si j’ai pas gagner je suis content de voir que film a été projeter et que des décideurs de même que d’autre jeunes du monde entier l’on regarder.Et ça s’était mon objectif.

Voici l’e-mail que j’ai reçu sur forum…

[see below]

LAUREL: Explain more about the forum in Geneva. Give me the whole name of the forum and tell me how you got to this point to present your film there.

TIDIANE: Even though I didn’t win I’m happy to see that the film was screened and that the panel and youths from around the world saw it. And that was my objective.

Here’s the email that I received about the forum:

http://www.ilo.org/employment/areas/youth-employment/WCMS_175301/lang–fr/index.htm

Dear Tidiane,

Congratulations! Out of the 240 video submissions we have received your video has been chosen as the top 15! Unfortunately due to tough competition your video has not made it to the top 3. Nonetheless, the great news is that your video will be featured on the ILO website and the ILO Facebook page (What about young people?). Also your submission will play in a video montage in the Cinema room during the Forum. In order to do this we ask you to send:

- Your video file (not link)

- For confirmation, provide your full name, age and nationality

In case you’re wondering, the winners of the ILO video contest will be kept as a surprise for the Youth Employment Forum 23-25! Once the three winners have had the chance to present their videos, the videos will be published on the ILO website and Facebook page (What About Young People?).

Thank you very much for participating in the ILO video contest! We look forward in sharing your video to youth around the world!

Kind regards,

The Youth Employment Programme

LAUREL: Tu as a choisi a donner le sagesse au personnage qui vient du paysage et qui porte les vêtements traditionnels. Partagez plus sur tes motivations pour cette choix. Est-ce que tu as voulu faire une déclaration sur les normes de genre aussi?

TIDIANE: Lui, c’est mon grand frère et il n’a pas de travail donc je savais qu’il était le mieux placé pour restituer tous ces sentiment des jeunes sénégalais qui sont dans la même situation que lui.Le problème dans nos pays est que le secteur primaire qui devait porter notre développement est reléguer au second plan et les jeunes qui habitent dans ces régions sont obligés de venir dans les villes à la recherche de travail, on appel cela l’exode rurale alors que si l’état avait mis l’accent sur l’agriculture, la pêche et l’élevage cela ne serai pas arrivée. J’ai donné plus la parole à cet homme parce que les dirigeants pensent que ces gens ne savent pas ce dont ils ont besoin parce que la plus part d’entre-eux ne sont jamais aller l’école donc ils doivent écouter et appliquer les politiques des intellectuels qui sont complétement déconnecter des réalités du terrain.Alors j’ai fais du sunukaddu, il faut que les principales concernés c’est à dire les jeunes puissent dire de quoi ils ont besoin.

LAUREL: You chose to give the wisdom to the person who comes from the countryside and wears traditional clothes. Share more on your motivations for that choice. Did you also want to make a statement on norms for this type of person?

TIDIANE: Him, he’s my big brother and he doesn’t have a job, so I knew that he was the best suited to voice all of the sentiments of young Senegalese who are in the same situation as he is. The problem in our country is that the sector that most needs development is relegated to the second tier, and the youths who live in these regions are obligated to leave their villages and look for work [in the big cities] — we call that the rural exodus. If the state focused on agriculture, fishing, and raising livestock, then this wouldn’t happen. I’ve given voice to this man because [the nation’s] leaders think that the [common] people don’t know what they need since the majority of [these common people] have never gone to school. So, [the leaders] think that they should listen to and apply the policies of intellectuals [instead of the hardworking Senegalese, even though the intellectuals are people] who are completely disconnected from realities on the ground. That’s why I do Sunukaddu, because its main principle is that youths [know and] can say what they need.

LAUREL: Quels roles ont-t-ils jouent tes experiences avec RAES (Sunukaddu, Clic Info Ado, etc) dans la realisation de ce projet?

TIDIANE: Beaucoup, j’ai fait preuve de conscience sociale pour pouvoir écrire le scénario, j’ai utiliser intelligence collective pour réaliser le film et je suis entrain de faire du réseautage pour que plus de monde puisse accéder au monde et le partager.

LAUREL: What roles did your experiences with RAES (such as youth programs Sunukaddu, Clic Info Ado, etc) play in the direction of this project?

TIDIANE: A lot. I showcased social awareness in being able to write the script, I used collective intelligence to direct the film, and I’m in the middle of networking so that more people in the world can have access to this film and share it.

LAUREL: Decrivez tes reves: 1) pour ce film; 2) pour la question d’acces a l’emploi; 3) pour les jeunes de Senegal; 4) pour ta carriere/vie.

TIDIANE: Il y a un grand penseur américain du nom de John Barth qui disait que : Ce n’est parce que tes rêves sont hors de porter que tu ne dois pas te donner les moyens de les atteindre.Mon rêve ce n’est pas de changer le monde, je sais que je ne pourrai pas mais je ferai de mon mieux pour aider le maximum de personne.Mon rêve est de voir ces jeunes se permettent d’avoir des rêves, de croire à l’Afrique .Mon rêve pour ce film est que les bailleurs qui aident nos pays puissent le voir et orienter les aides vers les populations surtout des zones rurales.Et cela les américains l’ont déjà fait avec le MCA (millenium challenge account) qui intervient dans les zones rurales.

Personnellement, je rêve de faire de grands film, qui seront diffuser dans le monde entiers parce que je pense que nous avons beaucoup de chose à partager avec le reste du monde .

Et pour ma vie de raconter une femme qui partages les mêmes rêves que moi, les rêves d’un monde meilleur ou toutes les personnes auront des rêves.

LAUREL: Describe your dreams: 1) for this film; 2) for the question of access to employment; 3) for youths in Senegal; 4) for your career/life.

TIDIANE: There’s a great American thinker named John Barth who said that, Just because your dreams are beyond your grasp doesn’t mean that you don’t have the means to attain them. My dream isn’t to change the world, I know that I can’t, but I will do my best to help the most people possible. My dream is to see that youths can realize their dreams, can believe in Africa. My dream for this film is that the donors who help our country can see it and direct their aid towards certain populations, especially in rural zones. And that’s what the Americans already did with the MCA (Millennium Challenge Account) that goes to rural zones. Personally, I dream of making great films that will be distributed around the whole world because I believe that we have a lot to share with the rest of the world. And, for my life, [I want] to meet a woman who shares the same dreams as me, dreams of a better world where everyone will realize their dreams.

To say that I feel the utmost respect for Tidiane Thiang is a woeful understatement.

It is my honor to have made Tidiane’s acquaintance and to follow his brilliant trailblazing from afar.

Tidiane, you are an inspiration. Thank you.

P.S. An email from Tidiane, dated February 6, 2012

Je pense que l’école dans laquelle vous avez expérimenté le projet [Robert F. Kennedy Community Schools in Los Angeles] à les

mêmes caractéristiques que la plus part des écoles aux Sénégal.Les jeunes

quittent l’école très tôt au Sénégal parce qu’ils n’aimes pas le cadre

formel dans lequel ils sont confiné, alors ils préfèrent allez dans le

secteur informel pour apprendre des métiers artisanaux ou devenir des

vendeurs à la sauvette dans les rues de Dakar. Dans les salles

informatiques des écoles au Sénégal, ont interdit aux jeunes aussi d’aller

dans les réseaux sociaux comme Facebook est cela a entrainer une baisse de

la fréquentation les salles informatiques.Je pense qu’il faut réfléchir

sur comment adapter les nouveaux technologies à l’éducation formel.Les

jeunes sont de plus en plus exigent et adapter leurs besoins au secteur

formel sera le pari des années à venir.C’est dommage qu’avec le taux

échantillonnage faible que vous avez, une évaluation fiable n’a pas pu

être fait mais ça serai intéressant de tester cette approche novateur sur

beaucoup plus de jeunes et voir l’impact.

Je pense que nous allons intégrer dans nos prochaines sessions de

formation les 4c(connexion-création-

que c’est très intéressant de renforcer la culture participative mais

surtout en se basant sur le ORID qui incite les jeunes à discuter .

C’est très gentil à toi de partager cette expérience parce qu’elle nous

ouvre d’autre perspective d’exploration local avec des jeunes de condition

sociale similaire mais de culture différente.